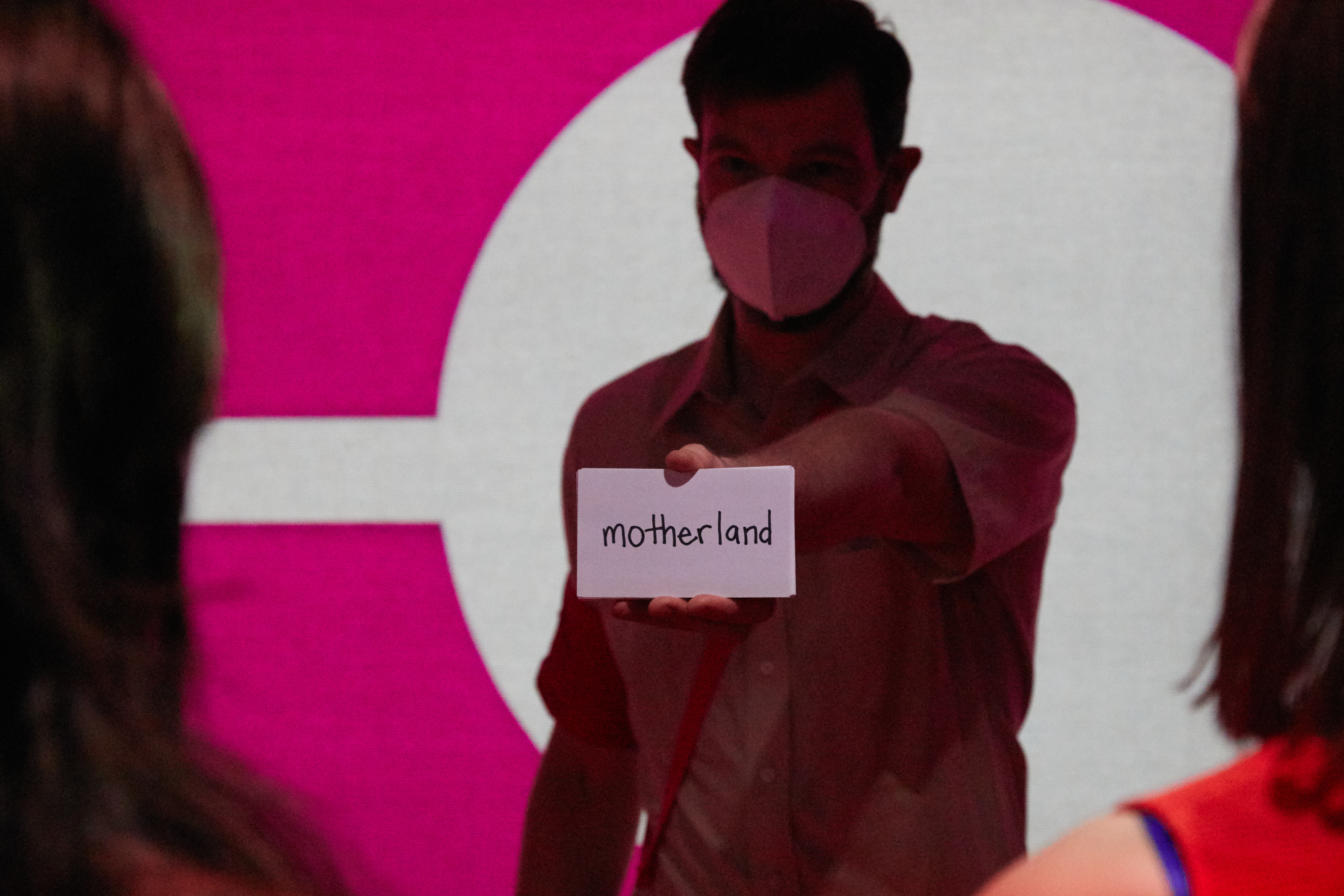

Everybody is Gone is an immersive art performance and research project co-created by Uyghur artist Mukaddas Mijit, U.S. journalist Jessica Batke, and The New Wild, a multidisciplinary art lab.

The live event combines elements of journalism, live performance, and museum exhibition to provide audiences with a unique perspective on the ongoing crisis in the Uyghur Homeland. The website and research database contains testimonials from Uyghur people living in the global diaspora, reporting from reputable independent media, academic articles, and official Chinese government statements, regulations and social media posts. That wealth of material provided the factual underpinnings for the events audiences experience during a performance of Everybody Is Gone.

We spoke to Mukaddas and Jessica about how the project came together, and some of the challenges invovled in doing so.

What is the project about?

Everybody Is Gone aims to help audiences understand, in some small measure, what is happening in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (in northwest China). Rather than do this in an information-dense, didactic manner, we wanted to reach people viscerally through a first-hand, immersive experience. Our actors interact with participants one-on-one and in group settings. In this way, we explore themes and mechanisms of control, surveillance, and group dynamics. We hope this experience gives our audience members the ability to connect some universal ideas and emotions to the very specific situation in the Uyghur Region.

Underpinning the entire experience is a database comprised of international reporting and academic articles covering the region. We wanted participants to know that we’re drawing directly from real life to create the environment they interact with in Everybody Is Gone. We also wanted to give audiences the chance to explore and learn more on their own if they are so inclined.

We premiered Everybody Is Gone in Berlin in 2022 and are looking to take it elsewhere in Europe in 2024.

Photo credit: Everybody is Gone/The New Wild

How did the idea originate?

We were casting about for ways to raise awareness of the treatment of Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in China. This was back in 2018 and 2019, just as international reporting on the issue was starting to pick up. We wanted to reach audiences who might otherwise not be engaged with international affairs or human rights. We believe strongly that art has an important role to play in both initially piquing someone’s interest and then affecting them emotionally in ways that traditional journalism or scholarship cannot.

The initial concept involved moving through a single Kashgar city street as it changed over the course of several years. We wanted audiences to see the outward signs of Uyghur language and culture disappearing – and eventually, the people disappearing too. This idea, of course, would have required far too much space and material! So we eventually settled on a smaller – though still quite expansive – concept that centers much more on participants interacting directly with authority figures, and only gradually revealing to them where they are and what exactly they’re participating in.

Photo credit: Everybody is Gone/The New Wild

Tell me more about how the collaboration happened or was facilitated?

The collaboration really centered on uniting fact, feeling, and lived experience.

Mukaddas brought her own personal history to the project, in addition to her extensive work in live performance and her training as an anthropologist. It was critical that we had an “inside” perspective to ground us in what we were doing. Did doing X feel true to Mukaddas’s own memory and life? How would doing Y or Z resonate with a Uyghur audience member?

Jessica approached the project as a fact-checker would, making sure that we could point to real-life examples for anything that happened in the show–sometimes directly translating from the Chinese government’s own reports. She could also stand in for an average non-Uyghur audience member to ask whether or not certain elements or techniques would make sense to someone without a personal relationship to the material.

The New Wild, a multidisciplinary art lab, was a fantastic place to bring those ideas, and to connect them with a larger group of artists to more deeply explore them.

What allowed us to work together despite such different backgrounds–and despite the challenges presented by living on different continents during a pandemic–was a shared commitment to bringing this story to new audiences, and a shared belief in the power of art to do it.

How long did it take to produce?

Years! Some of that was due to the pandemic. But it was also because what we were creating was something of a new form. There weren’t a lot of off-the-shelf examples of what “immersive journalism” might look like, so we had to take time to come up with something that we felt was both emotionally powerful and intellectually rigorous.

What were some of the challenges?

One of the biggest ones was understanding what audiences need and want, which aren’t necessarily the same things. Over time, we discovered that even if audience members want their experience wrapped up in a neat bow at the end, doing so may not be the most effective way to ensure that they stay engaged and activated on this issue even after they leave the theater. We also had to find ways to make sure that audiences felt they could leave the theater at absolutely any time, while at the same time nudging them to continue on in what can be an emotionally draining experience.

What was the most gratifying result?

Hearing from attendees that they are still thinking about the experience days or weeks later.

What is one lesson from this project that you would like to pass on?

This is going to sound really simple but it really is the heart of it all: taking a distant-seeming political crisis, and turning it into a deeply personal and human story, one that audience members can connect that to their own lives – it’s really, really hard.

Photo credit: Everybody is Gone/The New Wild