Black Box, or ‘Musta Laatikko’ in Finnish, is the live journalism production of Helsingin Sanomat, the largest daily newspaper in Finland.

Since 2016, Black Box has been bringing more than a hundred journalists and photoragraphers on stage to perform their stories in front of a large live audience. They have staged 21 unique productions in the last seven years, attracting an audience of more than 60,000 for those shows, including one production designed and performed especially for kids. They also produced the world’s first handbook on live journalism that documents their insights, learnings and best practices as part of a three-year-long research project on the power of live journalism.

One unique aspect of Black Box is the work of their production team member Kaisa Osola, a speech coach (and former journalist) who works with the journalists to prepare them for their performances. In this collaboration case study, we spoke to Kaisa about how her role came to be, how she works with journalists to prepare them for their performances, and the differences between telling a story in writing and in speech.

Black Box 17 team at the Finnish National Theatre in April 2022. Kaisa Osola is first from left in the back row. Photo credit: Rio Gandara / HS

How did your role come to be?

Kaisa said there were three reasons why the editors who started Black Box called her. The first was that, having worked on previous projects together, they were already familiar with her expertise both as a public speaking coach and a magazine and radio journalist. The second was that “they understood that with the scripts in their hand, what they had were texts, and text is a different genre than speaking”. The editors recognized that they needed help transforming their stories from one genre to another.

Lastly, as one of the Black Box producers told Kaisa: “Everybody is scared to death. Can you come here with your authority, and tell them that it’s enough that they speak as themselves?”

Anni Pasanen spoke about the world's most popular intoxicant, caffeine, which she also brought to the stage as a powder in a big. Photo credit: Kalle Kaponen / HS

How you work with a reporter?

In a Black Box production, every speaker is assigned one of the three editors in the production group to work with them on their story, as well as the visual producer of the show. In the beginning, Kaisa worked a lot with these editors, who all came from a writing background, and gave them checklists and advice for editing for speech. Over the course of the past seven years, these editors have become professionals in editing for speech as well.

“What I always start with is that public speaking is not about acting or transforming yourself as a human being. It’s about the right verbal and right non-verbal communication,” Kaisa said.

She always begins by asking the jouranalist: “In a single sentence, what is this story about?” It’s critical to condense the crux of the story into a sentence because “in speech, you can put significantly less stuff than in a text, so we really have to narrow down the amount of information that you put there.”

The second question is: “So what?” There are many ways in which a story can be meaningful to an audience, “but these are the things that the journalists don’t necessarily put into the text even if they do consider them carefully in their minds and as a part of the journalistic process,” Kaisa said. The temporal element is also important, so she follows up by asking “Why now?” For the audience attending a show, “the speech is unique. It’s live, it’s something happening now. it’s not [an event] that happened, say, a year or even a month ago.” So even if reporting and the events described happened in the past, the journalist will need to find a way to make their story relevant to the audience in that very moment.

The answers to these questions are important for establshing the ways in which the audience could potentially connect with the story. Equally important for this connection, Kaisa said, is to show the journalist’s own involvement with the story.

“In the speaking genre, the listener always thinks: How did you know that? Where did the information come from? Is it credible? Why do you want to talk about this? So what we really have to bump out from the journalist is [their reporting process, e.g.] ‘I made 200 telephone calls’, or ‘At this point of the story I just thought it was going to be impossible’. It’s about establishing the interest and credibility of the speaker, and you have to say these things out loud.”

Photo credit: Rio Gandara / HS

Other parts of the coaching are about the delivery on stage: The right moments to pause, remembering to smile, looking at the audience with a respecting, curious mindset and projecting their voice. “Some of the listeners are 70 meters away, so even if you have a microphone you need to speak to them with the same intensity and warmth as if you’re talking to your friend across a football field,” Kaisa said. “It’s about getting comfortable, and having the understanding that if it feels stupid, it doesn’t mean that it looks stupid.”

What can make the collaboration difficult?

“At the end of the day it’s about the content,” Kaisa said. Whether a collaboration is difficult or not depends on whether there “is an interesting story or interesting information. Is it something that the speaker actually has an ownership to and a motivation of telling? We have become quite strict [in requiring that].”

Two other factors that might get in the way of a successful performance are the language (it doesn’t work if the text “stays in too written a form”) and the time needed for practice. “In order to be as confident as possible, you need practice, and sometimes people are very busy. But it doesn’t really happen these days [that journalists performing in Black Box wouldn’t prioritize preparing for the performance]. People understand that the better you know it, the better you can present.”

What do you find most gratifying about your work?

“Live journalism does good for journalism, she said. “Because once you open up about where the information comes from and why you want to tell the story then it’s more transparent and more interesting. These elements stood out also in the large audience study of the research project.”

“When a person whose profession is not to speak in front of hundreds of people speaks in front of hundreds of people [and they are] shaking, anxious but telling something that is very interesting and well-crafted…that’s a concept that sells out the biggest theatre in Finland half a year before they even know what the content is about to be.”

“It’s a symbol of what public speaking can be. Powerful and vulnerable at the same time. Reachable to anyone. It gives hope.”

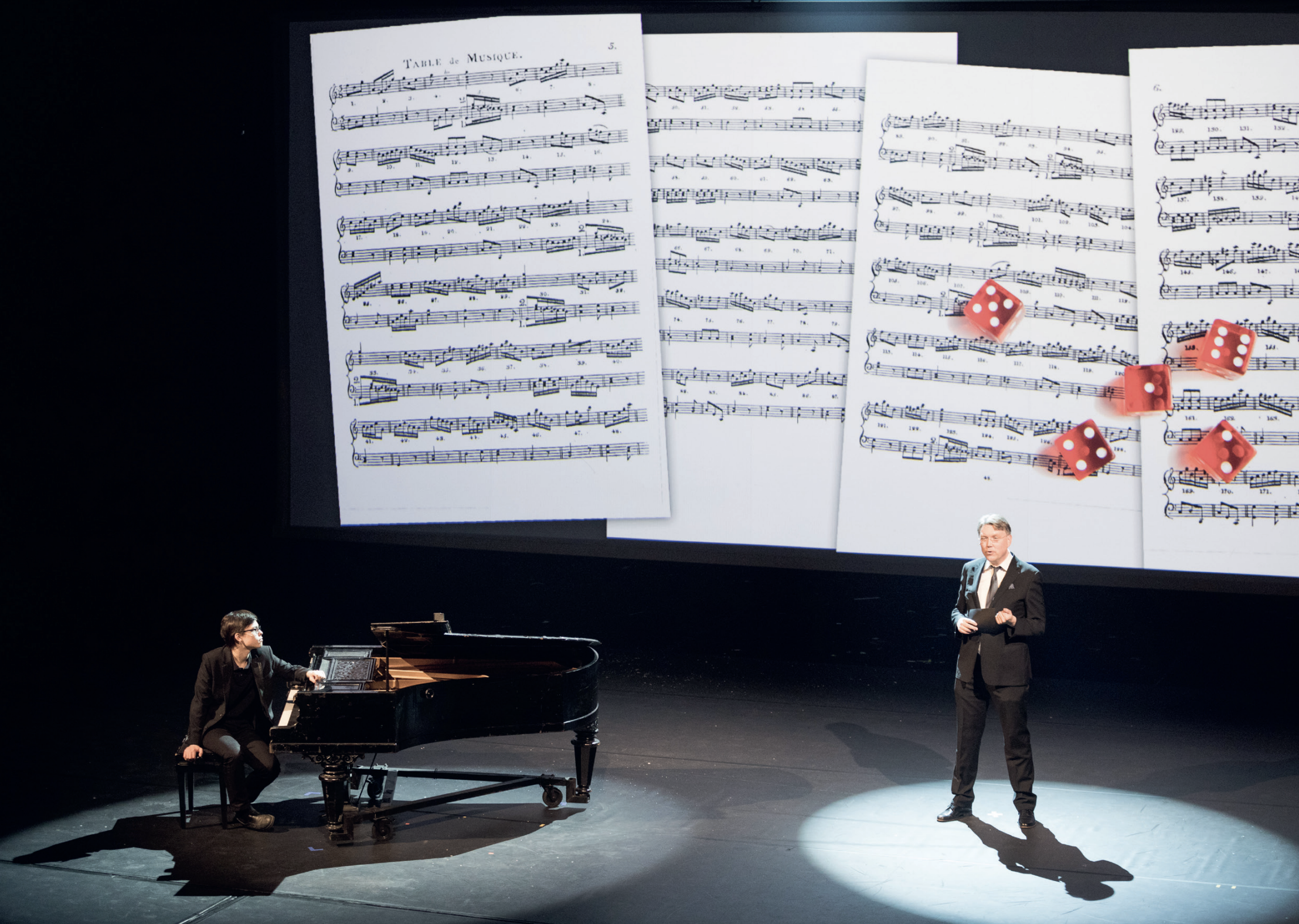

Vesa Sirén's speech focused on music composed by artificial intelligence. Photo credit: Valtteri Heinonen / HS

What tips or lessons do you have for reporters interested in performing their stories live on stage?

Kaisa had several tips for budding live journalism performers:

- Good live journalism is about good public speaking

- Public speaking is a skill, and the only credible, interesting and fascinating way to do it is as yourself

- Extend your comfort zone in non-verbal communication so you’re not just reading from your notes

- Respect the listener and show it both verbally and nonverbally

- Think big when considering how to illustrate your speech or how to visualize it

- Dare to be human and vulnerable