I gave this talk at the ECREA Journalism conference in Utrecht on June 17. It was part of a panel on Designing for deeper audience engagement that brought together researchers and journalism practitioners to discuss questions concerning the design for deeper audience engagement. The panel covered topics such as metrics, interactive formats, and finding a balance between audience-journalist participation.

Hi everyone. I’m Robin Kwong, New Formats Editor at the Wall Street Journal and it is my honour to speak to you today about designing for audience engagement. In particular, I’m going to talk a bit about some of the tensions we found between designing news experiences for engagement and certain traditional journalistic principles.

You heard a bit earlier in the panel about the Uber Game, which we made when I was at the Financial Times. The Uber Game is a newsgame about being a full time Uber driver that takes place across seven in-game days. When we were producing the game, we tried really hard to make it fact-based, and to follow all the steps and rules of journalism that we would take if we were writing an article instead of making a game.

In practice, this meant interviewed dozens of Uber drivers both for their anecdotes that we used for the scenarios, and also for structured data that would underpin the simulation. We read economic papers modelling the Uber economy, and when the game was close to being ready, we showed our model to Uber to ask them for comment (and also because, obviously, they have the access to the real numbers).

In short, we tried really hard to make the Uber Game an objective, fact-based piece of journalism.

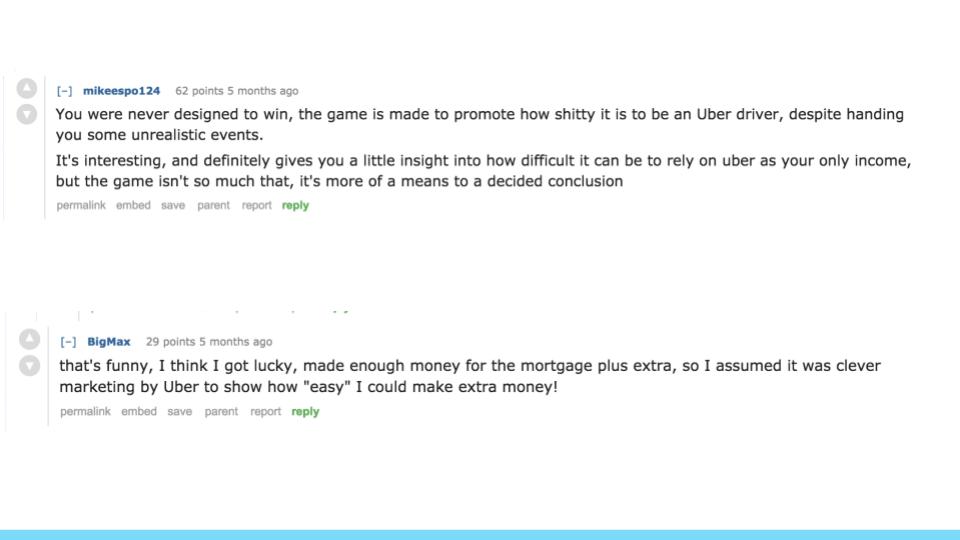

But something interesting happened after we published. A link to the game was posted to Reddit, and as people played the game, they started commenting in the thread.

One person - mikeespo124 - said the game was, basically, anti-Uber propaganda. It’s rigged so that the player would always lose. It’s not objective, and Mike clearly thought that what we created was a piece of persuasion and not journalism.

But what was even more interesting was that within the same thread, literally just a few comments down from Mike’s objections, was this comment from BigMax, who basically said the opposite. BigMax thought that we created a piece of pro-Uber propaganda. Again, the assumption is that they had encountered a piece of persuasion or marketing rather than objective journalism.

~~

How could these two people come to such wildly different conclusions even though they played the exact same game? This is because they wrote their story of what happened in those seven in-game days. They made different choices, and therefore encountered different outcomes.

This is a key feature of interactive formats. Instead of the author controlling most of the news experience, we invite the audience to become co-authors and co-creators. The magic of narrative games happens at that meeting point between the system that we have set up, and the stories that the players craft within that system.

I’m a huge proponent for creating these types of experiences, but I think it is important to ask: To what extent are interactive news experiences like the Uber Game objective? To what extent is it impartial? And, even, to what extent is it journalism?

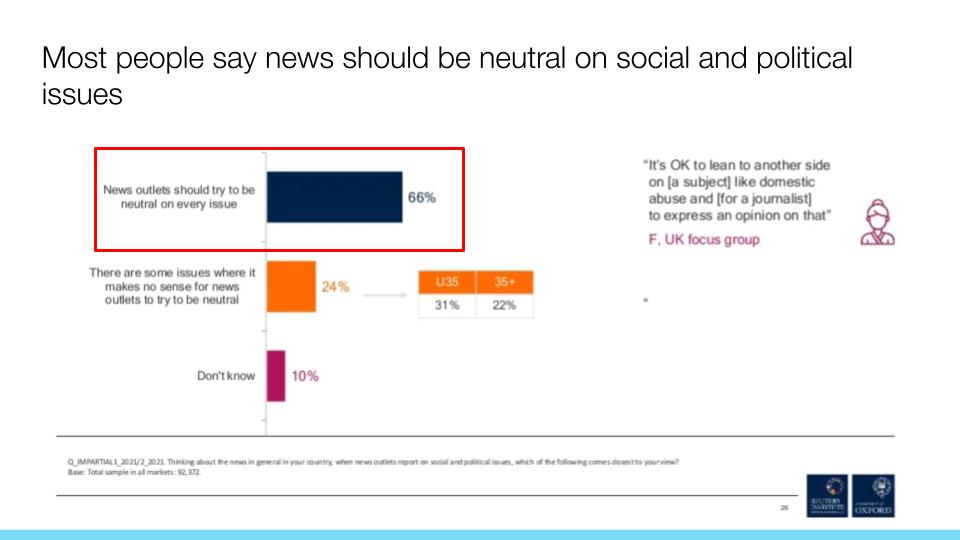

These are critical considerations because, however they define it in their own minds, impartiality and objectivity are what most people want from journalism, as the Reuters Institute’s annual digital news report survey has consistently shown.

More importantly, this tension does not only exist in news games. It exist whenever we introduce interactivity to the news experience, and whenever we design for audience engagement and agency.

In those situations, we are relinquishing some of our control as authors to enable co-creation, which in turn creates a different type of experience. For example, as a previous panel noted, this enables news games to create transformative learning experiences that are not possible with traditional, static formats.

On a larger scale, this tension also exists when we are designing entire news organisations from the ground up, where the basis of trust is relational and is meant to come from enabling audience agency.

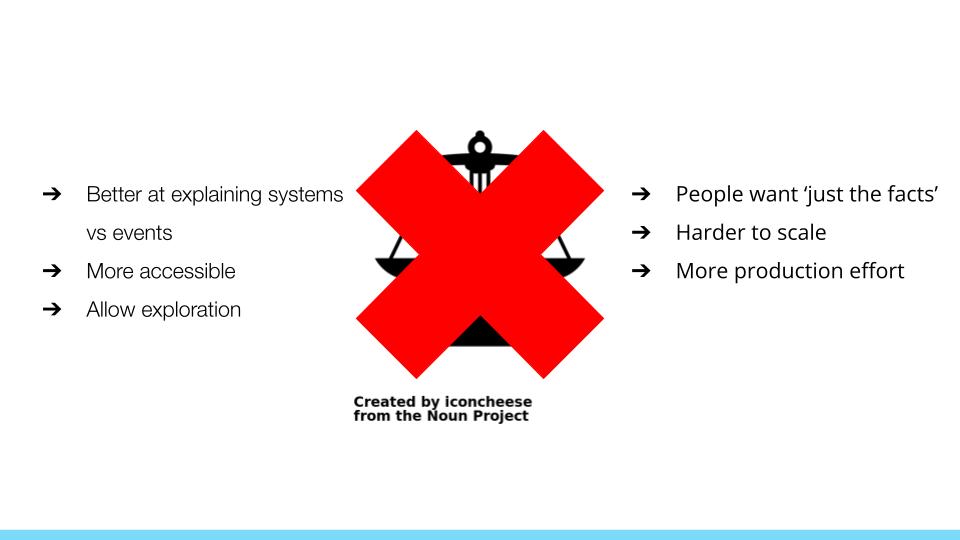

So how do we resolve this tension? I don’t think it can ultimately be done by considering it purely as a matter of journalistic trade-offs, or of considering the pros and cons to interactivity and engagement within journalism itself.

Instead, we have to consider interactivity in terms of the broader mission and (to hark back to the opening statement) the overall objective.

When we do this, we are forced to grapple with the evolving role of journalism in society, and how journalistic skills, practices and norms can be brought to service across a much wider range of activities and spaces than traditional, objective journalism.

I don’t have the answer as a practitioner, but I think the true value of interactivity can only be unlocked in quasi-journalistic terms, and that is increasingly what I am personally drawn to: How can journalists help create public art? How can journalism bring a foundation and a shared understanding of reported facts to community spaces - for communion, for healing, and for social change.